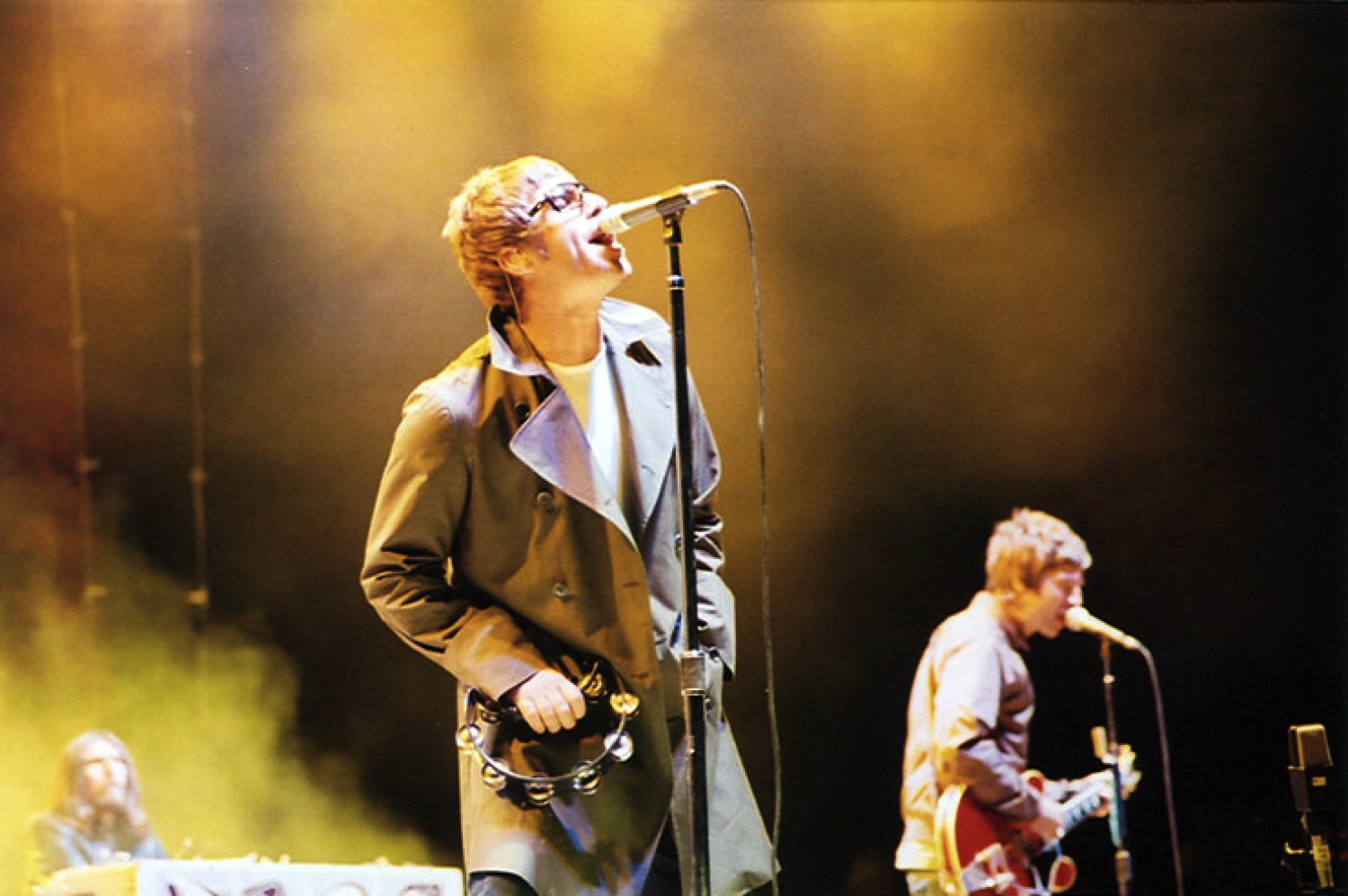

Queue Controversy 2024 : Comment Oasis a réuni la Grande-Bretagne dans la frustration

Image attribution: Will Fresch, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

If you’re not intimately familiar with the UK, you may be confused as to why Oasis was trending last month. Well, it was a perfect blend of some of Britain’s favourite things: Britpop, queuing, and complaining.

In summary, one of Britain’s best bands announced a reunion tour. Hundreds of thousands of people tried to get tickets, which led to them waiting for hours in an online queue. When they reached the payment section, many found that the available tickets cost more than they were expecting.

Needless to say, people weren’t happy.

Squaring a circle

Ticket queue controversies aren’t new. Before the Oasis debacle, it was Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour that made headlines. As we go to press, there are already complaints regarding Coldplay’s ticket sales.

It sounds like a simple problem: more people want tickets than the available amount.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a simple fix. An overwhelming amount of people want to see a single artist. This means that there needs to be a queue solution on a website; otherwise, it will crash.

Moreover, it simply isn’t possible to give everyone a ticket at the price they want, so queues become a way to ration tickets. The alternative is an auctioning process – but that’s even less popular.

So, given the limited supply of tickets at a set price, queues become high-stakes for customers. When some don’t get tickets, queues become the focus of their ire.

At the core of this problem, artists don’t want to be seen by others as exploiting their fans. Tickets, therefore, are never first listed for their true market value.

Not only does this create an opportunity for scalpers to buy and resell tickets for much higher prices, but it also means that artists can raise prices through Ticketmaster when they see the size of the demand.

A psychological problem

So, while the problem initially related to queuing, many turned their attention to dynamic pricing. Was it fair that the price changed while people were waiting?

The UK culture secretary didn’t think so. Lisa Nandy described the situation as “very depressing” and pledged to bring in preventative measures. Speaking to the press, Nandy said:

“We will include issues around the transparency and use of dynamic pricing, including the technology around queuing systems which incentivise it, in our forthcoming consultation on consumer protections for ticket resales.”

As mentioned, prices are driven by supply and demand. While artists might not want to be seen as ripping off their fans, they certainly benefit from dynamic pricing.

The problem, however, is psychological. Once someone has entered the queue and committed their time, they’ve made an implicit commitment to buy the tickets at the listed price – else they’ve wasted their time once they get to the front.

From the perspective of the customer, the queue is part of the buying experience – a rational decision to wait based on their queue number and the possibility of tickets being available at the price at which they joined the queue by the time they reach the front.

In the customer’s mind, the vendor made the offer once they saw their queue position. They’re just waiting their turn.

For many vendors, the queue is also a protective shield – something to stop the website crashing and a way to coordinate customer purchases. However, to them, the customer has not actually entered the buying cycle until they reach the front, so shifting prices before that is fair game.

So, who needs to change their view: the customer or the vendor?

Either way, many people won’t be getting tickets.

Is this in bad faith?

Queue numbers don’t equal ticket numbers. Sometimes issues happen (although it was funny seeing Varnish errors become a meme on my social media timeline – thanks, algorithm).

Moreover, demand was overwhelming, even without the Varnish errors. Many people didn’t like having to queue before joining the main queue. Whatever Ticketmaster had originally provisioned for capacity was likely breached that day.

The alternative to this is a free-for-all. Let’s say Ticketmaster could provision enough capacity to let everyone on the site at once. Seats would disappear before peoples’ eyes or by the time they get to checkout.

In a matter of seconds, there would be nothing left. Most would walk away empty. Wouldn’t that generate a set of headlines anyway?

Alternatively, tickets could be distributed by lottery. It’s not clear that people would like this either. At least queues have an element of fairness and organisation – first come, first serve.

Tickets could be auctioned instead, but this would undoubtedly raise accusations of fan exploitation.

No such thing as bad PR

Perhaps it comes down to the fact that many people simply can’t rationalise millions queuing at once. If you show up to a physical venue on time and see hundreds of people queuing around you, it makes sense that they got there before you (how else would they be there?).

But, in the virtual world, millions of people can materialise somewhere at once. So, queues are inevitable. It’s how a distributor chooses to handle it that causes problems.

Some people suggested returning to physical ticket sales sold in shops. It’s not a real solution to the problem – just a desire for people to see queue numbers in ways they can visualise. The problems of excessive demand and resellers don’t go away.

Perhaps a shift in view is needed. Vendors should look at their queue as part of the customer’s buying experience rather than just an “offload mechanism”. Instead of keeping users in the dark, they could share information about availability and pricing in the waiting room. Users will not feel as though they committed to queuing under false pretences.

While this won’t solve the problem of limited supply, it would increase transparency throughout the entire vending cycle.

Either way, the spectacle kept Oasis in the headlines for three days – perfect publicity for when they announced extra touring dates. According to Oasis, they will sell these tickets by lottery (which has its pros and cons).

Queues or lottery, Crowdhandler does both. To see how CrowdHandler in action, sign up for free.